New Approaches to Short Fiction and Nonfiction in the Classroom: Challenging Violence from Queer and Straight Perspectives

The short story and nonfiction essay are on the front line of the #MeToo movement. Take Kristen Roupenian’s short story “Cat Person” and Ocean Vuong’s “A Letter to My Mother That She Will Never Read,” which were published online around the time that the #MeToo movement gained momentum in 2017. Roupenian’s story about a disturbing sexual encounter taps issues of consent that began to be talked about in complex ways in light of #MeToo, while Ocean Vuong’s essay about domestic violence offers the subjectivity of a Vietnamese American, queer man. These stories counter understandings of #MeToo as highlighting only particular kinds of violence that happen to white, straight, cisgender women (cf. White 2017)—thus returning to the intentions of its originator, social worker Tarana Burke, as a means to find solidarity with black girls who had experienced violence (cf. Garcia 2017). This essay will offer strategies and models for using nonfiction essays (by Vuong and Carmen Machado) and short stories (by Roupenian and Eileen Chang) to ask questions about violence as an act impacted by institutions and cultural narratives, while showing how specific literary strategies allow writers to challenge assumptions about how violence works and how it is experienced. [Read the full article in #MeToo and Literary Studies: Reading, Writing, and Teaching about Sexual Violence and Rape Culture.]

Toward the Ekstasis of Rilke’s Angels: The Value of Depression in Gwyneth Lewis’s Poetry and Memoir

In ‘Poetry and Therapy,’ the psychotherapist J.K.W. Morrice describes the usefulness of poetry for the sufferer of depression and provides a thought-provoking and decorous metaphor. The depressive patient writing poetry is, Morrice explains, “[l]ike the chrysalis … [that] survived the typhoon and, metamorphosed, began to flutter her wings with some surprise, but with a sense of freedom and purpose” (1983, p. 370). Poetry is often invoked as a catalyst for metamorphosis from despair to hope, from desperation to redemption. David Wojahn traces a vein of poetry about depression, noting the “tradition of mad British versifiers” from John Clare onwards, contrasting the British lineage with the American “middle generation” – Sylvia Plath, John Berryman, Robert Lowell et al – who all “suffered bouts of acute mental anguish resulting in extended hospitalization” (2005, p. 113). The act of writing through depression, however, is far from easy when one aspect of the illness is a “mind-numbing lack of engagement with the world” (Wojahn 2005, p. 115) Wojahn asks: “How do you write poetry at a time when even tying your shoes seems a Herculean labor? And how do you talk to someone about such a frightening predicament?” (p. 115). These questions are answered, at least in part, by author Gwyneth Lewis (born 1959); depression is the subject of her memoir Sunbathing in the Rain: A Cheerful Book about Depression (2006), and her series of poems “Chaotic Angels.” [Read the full article in Re/Imagining Depression: Creative Approaches to “Feeling Bad.”]

Still Devouring Frida Kahlo: Psychobiography versus Postcolonial and Disability Readings

When the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) hung Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait Fulang Chang and I (1937) in 2009, a unique decision was made. The curators resolved to hang the painting alongside a mirror that Kahlo had gifted to a friend Mary Sklar (as an accompaniment to Fulang Chang and I). In a blog entry for MoMA’s website Inside/Out, curator Veronica Roberts explains that ‘As a gesture of gratitude for a different painting Sklar purchased from the Levy show, Kahlo gave her this one, telling Sklar that she had added a mirror so that they could always be together’ (2009). For Roberts, Kahlo’s gift of the painting and mirror is ‘a fundamentally generous gesture—an open invitation to enter the work’ as ‘[w]e are invited to see ourselves (literally) and to enter her world’ (Roberts 2009). [Read the full article in Narratives of Difference in Globalised Cultures: Reading Transnational Cultural Commodities.]

What the Rape Survivor Should (Not) Feel: Redefining Trauma in Pascale Petit’s Poems about Deer, Birds and Butterflies

“The newly emerged atlas / perches on my hand, and it trembles – / like a new world, warming up for its first flight.” Welsh-French poet, Pascale Petit, is a poet of precariousness, of unspoken or hinted tension, of strange, disturbing feelings that emerge to unsettle the everyday and invest seemingly insignificant circumstances with meaning. The Atlas Moth that emerges from its metamorphoses (in Petit’s poem named after the creature) is not simply an insect being born, but an atlas or map. It is a fragile beginning or hope that might present the possibility of a ‘new world’ and the exhilaration of flight, a metaphor for the creative process. [Full article forthcoming in Devolutionary Readings: English-language Poetry, and Contemporary Wales, ed. Matthew Jarvis.]

Ekphrasis in a Convex Mirror: Decaying Monuments and Breathing Statuary in Kelvin Corcoran’s Writing about Art

In ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,’ the poet John Ashbery contemplates the longevity of art and considers what visual art conveys to a viewer about past artistic or public histories. Ashbery explains that ‘Each person / Has one big theory to explain the universe,’ but such a theory cannot ‘tell the whole story’ (Self-Portrait 81). This chapter admits Kelvin Corcoran’s inheritance from poets like Ashbery that challenge teleological certainty. The analysis concludes, however, that Corcoran’s ekphrasis is also in inflected by English Romantic models of ekphrasis, which challenge the permanence of art and its ability to preserve particular public legacies or personal histories.

[Read more in The Writing Appears as Song: A Kelvin Corcoran Reader.]

‘Male Fantasy, Sexual Exploitation and the Femme Fatale: Reframing Scripts of Power and Gender in Neonoir Novels by Sara Paretsky, Megan Abbott and Stieg Larsson’

In the classic retro-noir movie, Chinatown, the private eye, Jake Gittes, makes a significant statement regarding the dynamics of power between men and women in hard-boiled narratives. Ostensibly trying to reassure the mysterious Evelyn Mulwray, Gittes’s comment is extremely revealing about his attitude to the femme fatale: “Just tell me the truth. I’m not the police. I don’t care what you’ve done. I’m not going to hurt you, but one way or another I’m going to know”… [Read the full article in the edited collection Rape in Stieg Larsson’s Millenium Trilogy and Beyond.]

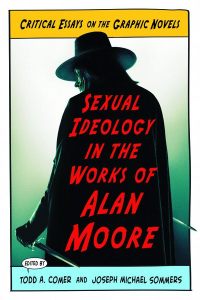

Theorizing Sexual Domination in Alan Moore’s From Hell and Lost Girls: Rippers of Desire versus Wonderlands of Desire

“With symbols man casts woman down, and then with symbols keeps her there” (Moore, From Hell 4, 24).In the comic book genre, women are routinely objects of violence. In 1999, the comic book writer Gail Simone set up the website Women in Refrigerators to document how women in comic book narratives tend to be “depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator.” The work of Alan Moore is no exception in presenting violence against women as an routine event. Moore, however, probes for the causes of physical, psychological, and sexual violence against women, from the perspective of both male perpetrators and female survivors… [Read the full article in the edited volume Sexual Ideology in the Works of Alan Moore.]

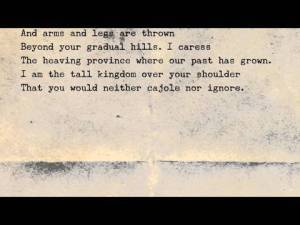

Feminism without Borders: The Potentials and Pitfalls of Retheorizing Rape (written with Sorcha Gunne)

We begin this introduction by citing ‘Act of Union’ by the Northern Irish poet, Seamus Heaney. The controversy and difficulty of representing rape is condensed in this poem where Heaney speaks from the point of view of imperial England which sexually and politically subjugates its colony, Ireland – the province of Northern Ireland is subsequently born from this union – with an act of rape… [Read the full article in the edited volume Feminism, Literature and Rape Narratives].

The Wound and the Mask: Rape, Recovery and Poetry in Pascale Petit’s The Wounded Deer: Fourteen Poems After Frida Kahlo

This chapter discusses the poet Pascale Petit (born 1953) and the cult Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), and it begins by noting that in the introduction to The Diary of Frida Kahlo (under the subtitle ‘Youth: A Streetcar Named Rape’), Carlos Fuentes describes how in Kahlo’s trolley accident in 1925, ‘A handrail crashed into [Kahlo’s] back and came out through her vagina. At the same time, the impact of the crash left Frida naked and bloodied, but covered with gold dust’ (1995: 12). For Fuentes, Kahlo becomes a subject both who is broken open in trauma (her accident being comparable to rape in

Fuentes’s view) and who becomes a work of art in her own right as the gold dust settles over her broken body. It is this conundrum that inspires Petit in her poetry chapbook, The Wounded Deer: Fourteen Poems after Frida Kahlo (2005)…. [Read the full article in the edited volume Feminism, Literature and Rape Narratives].

An introduction to the poetry of Jen Hadfield

In “The Poetics of Devolution,” the critic Alan Riach discusses how the creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1998 helped to redefine Scotland as an autonomous region of Britain with a burgeoning cultural and literary scene. Riach notes that Scottish poetry after devolution does not have to engage with Scottish nationalism as it once did; there is “room for dissent,” and within the new “polyphony” of Scottish poetry, Riach lists the writer Jen Hadfield (“The Poetics of Devolution,” p. 15). Hadfield is occasionally controversial in Scotland, because, being half-Canadian and half English, she brings to Scottish landscapes what the poet Tom Pow calls “an outsider’s eye” (“Jen Hadfield…,” p. 112). Hadfield is much admired by critics and other poets, however, for the genuine quality of her poetry, which takes sincere joy in her surroundings and in the rituals of ordinary people. The reviewer Stephen Burt suggests that though Hadfield tries to “sound wordly, even cosmopolitan,” her poetry is particularly powerful because of the freshness of its childlike view on the world (Burt, “Sound Sense,” p. 24). Pow recognizes this sense of novelty, too, but comments on the clarity and innovation of Hadfield’s images, which “have the freshness of the haiku about them” (Pow, “Jen Hadfield…,” p. 111). [Read more in British Writers Supplement XIII. ]

The Big Grey Ir-Elephant: The Play of Language in the Marx Brothers’ Scripts and in Charles Bernstein’s L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poetry

This paper explores the relationship between the linguistic experiments in the Marx Brothers’ scripts and the poetics of the American L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E movement. In an untitled poem from his collection Poetic Justice (1979), Charles Bernstein describes an elephant that ‘appears without the slightest indication that he is demanded’, a device that works to expose poetic linguistic practice as one kind of convention and to deny the authority of words as a means for an experiential journey. In the Marx Brothers’ scripts too, the image of the elephant is an irrelevancy, a red herring, a nonsensical diversion, a non-sequitur or an illusion that reveals the play of language and challenges its transparency. Bernstein recognizes a parallel between his poetic practice and the Marx Brothers’ wit in his own commentaries, and this paper seeks to explore this connection by comparing key speeches in Marx Brothers movies like The Cocoanuts (1929) Animal Crackers (1930), Horse Feathers (1932) and Duck Soup (1933), with poems from Bernstein’s Rough Trades (1991), With Strings (2001) and his libretto Shadowtime (2005) (which features Groucho Marx as a character). [Read the full article in the edited volume A Century of the Marx Brothers.]