Content warning: images of violence in advertising, mention of sexual violence, intimate partner violence and rape myths in the context of advertising campaigns and public messaging for anti-violence prevention.

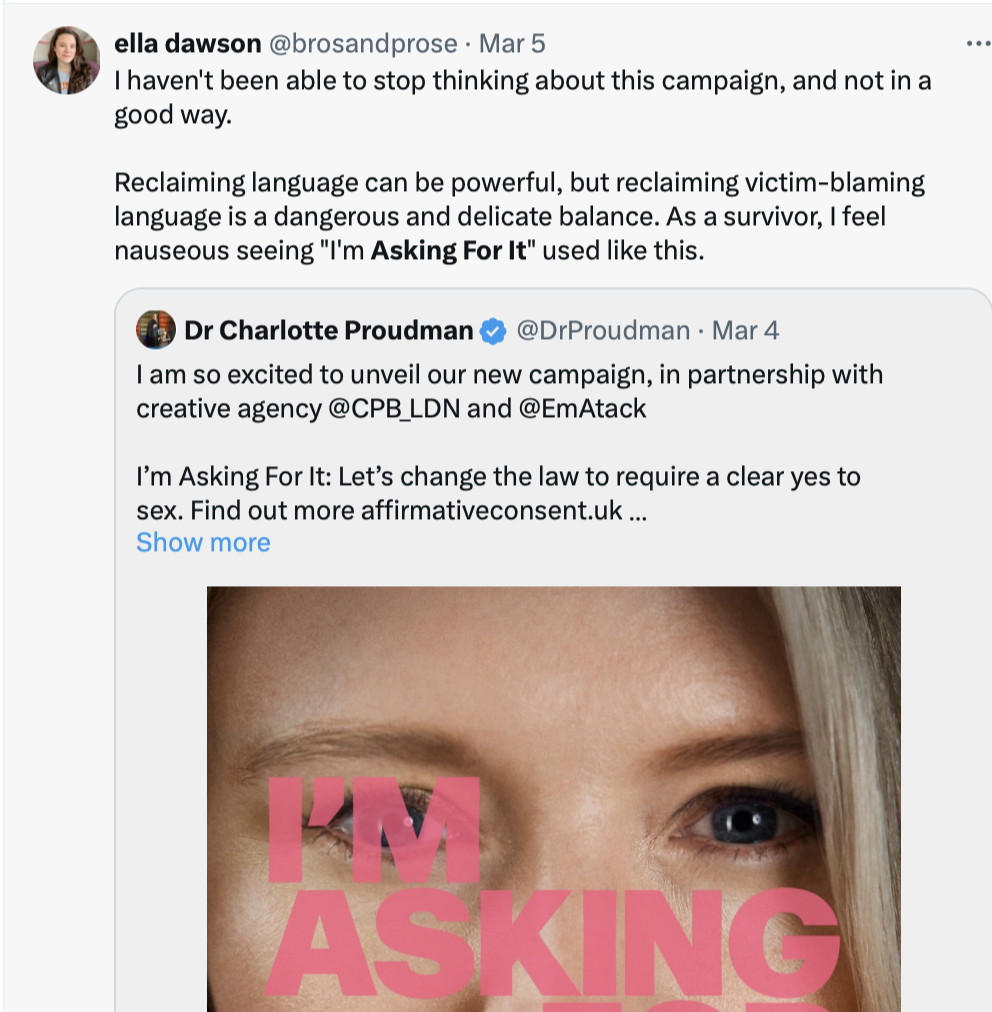

International Women’s Day is almost upon us, and I wanted to touch on a subject related to my anti-violence work and teaching. This week, CPB London and legal campaigning body Right to Equality launched a campaign to update laws in the UK surrounding sexual offences, demanding that they use an affirmative consent model. This campaign likely comes out of good intentions, but it is not the first time that the end result of campaigns like this is questionable at best.

The main image used to front the campaign posted and reposted on Twitter was a large, close-up photograph of a white woman’s face with the following words superimposed in large pink and white block caps: “I’M ASKING FOR IT. LET’S CHANGE THE LAW TO REQUIRE A CLEAR YES TO SEX.” Other versions of the poster use the faces of women of the global majority, but the white woman’s face seems to be the one posted most often, which seems a bit questionable and speaks to the problem of having people in the advertisement at all.

The idea of the campaign was to subvert the phrase “asking for it” which is often used in rape culture to blame people who have experienced violence. Rape myths find ways to blame people for the violence they experience because of their clothes, their behavior, being too friendly, being too unfriendly etc. etc. though of course the blame should always actually be on the perpetrator and their decision to harm or hurt another person.

One question is whether it is possible to subvert the phrase “asking for it” without any prior work, labour or campaigning. Is it likely to change its meaning overnight? And is the design of the poster for this campaign likely to propel that change? What about the choice of having the words superimposed in block caps over women’s faces for example? Is this an erasure of identity?

Many people have commented already and astutely on the problems of the message and how it is posed. In the original “asking for it” phrase, the “it” is rape – a person is asking to be raped – an extremely disturbing message. However, the supposed surprise of this campaign poster is that the “it” being asked for has now become “sex” or maybe the “it” is new laws? It’s unclear, but regardless sex itself while muddled is framed as something done to women, who are its passive recipients, and I’m not even sure if or how nb people or men who experience violence figure in this campaign.

It’s a very confusing and disturbing message overall. So Mayer put it well on Twitter, when they said: “the issue is the conflation of rape and sex. ‘Subversion of blame’ only applies to rape/coersive consent, not to affirmative assent to sex. The phrase doesn’t therefore ‘flip the script’, it implies that all sex is rape (& that rape is sex which it isn’t).”

People who have experienced sexual violence talked on social media about how they felt triggered and disturbed by the campaign.

Right To Equality suggested that they had talked to ‘survivors’ about the campaign, but it just goes to show that not everyone feels the same and so great sensitivity and caution are needed when designing these campaigns. Helen James at CPB stated: ““I’m Asking for It is an intentionally provocative body of work. We want to stop people in their tracks, get them thinking about how women are often treated by society and the courts – and the excuse used too often that they were ‘asking for it’.” So in short, the campaign is designed to provoke, and the people likely to be provoked are those who have experienced violence, potentially forcing them to relive their trauma. Too often, campaigns like this are insensitively designed and people who have experienced violence are the fodder for shock tactics or quirky strategies to catch the attention of the public.

Beyond objections about the campaign itself, there might also be a problem with the idea that consent is the answer to issues in the justice system when it comes to sexual violence. Emily Atack seems to have reasonable intentions when she states “Consent, or the lack of it, is at the heart of so much sexual harassment and violence that women and girls experience, yet the current law still fails to protect those who don’t say the word ‘no’ outright.” Consent however is complex and difficult to prove. Dr. Nicole Bedera notes that the affirmative consent model “encourages the listener to look for any evidence a victim was ‘asking for it,’ which quickly leads to slut-shaming. It deepens the very rape myths it’s supposed to upend.” Bedera also talks about deep problems within how the affirmative consent model is deployed: “One of the most alarming findings in my research is how affirmative consent has been weaponized against survivors. Instead of expanding the list of actions that mean ‘no,’ I found that investigators only looked for actions that they could consider to mean ‘yes’.”

In thinking about the problems of this campaign, I recalled some messaging which I worked on with students during my course on anti violence advocacy for Sexuality Studies at the Ohio State University. On that course, students had to come up with a campaign for the public good which was seeking to promote awareness and perform anti-violence advocacy. We looked closely at some messaging related to intimate partner violence with some lessons on what not to do which might be relevant here.

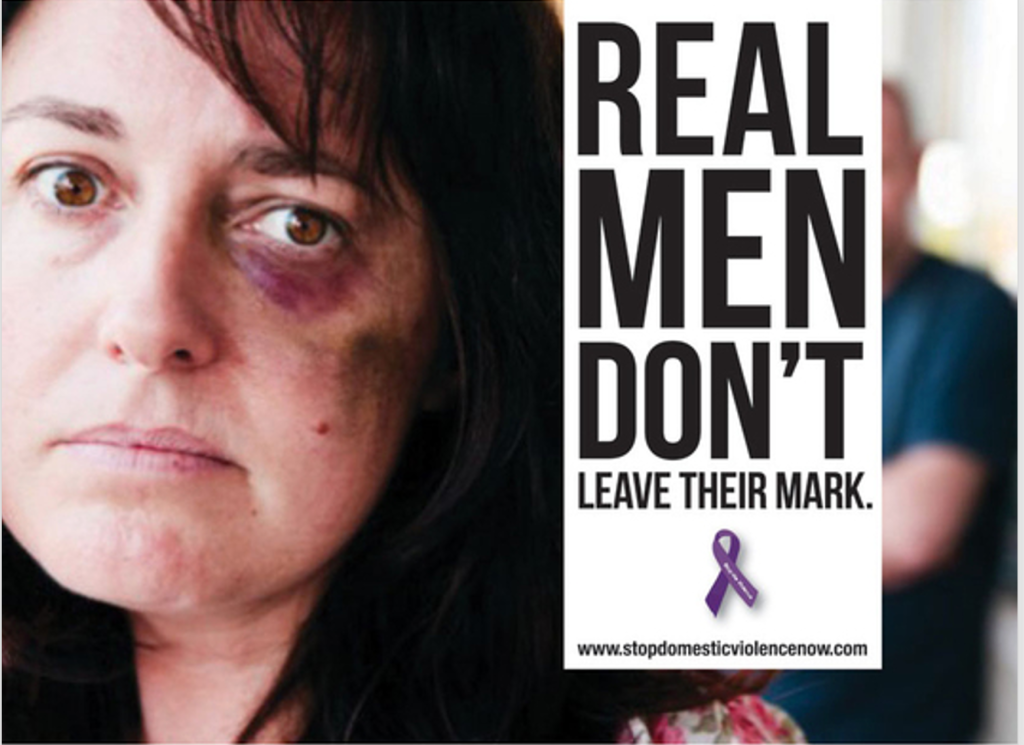

This campaign appears to be from Cameron County Texas, and like many other messages related to intimate partner violence, it uses imagery of beaten and injured bodies, which is problematic on a number of levels. It victimizes people who have experienced violence. It inadvertently suggests that only violence which has obvious evidence (bruises, cuts etc.) is valid or believable. By using the phrase “Real men”, it tries to play into norms of masculinity and notions of heroism, but it is not the most progressive tactic in suggesting that there are “real” men and other types of men who don’t live up to masculinity’s standards. Like “Asking for It”, the advertisement uses shock, though in the case of the recent campaign, it is people who have experienced violence who are most likely to be on the end of that shock. There’s a similar tactic in this next advertisement.

This professional campaign titled ‘The kitchen, The living-room, The day’ was published in France in November 2010. It was created for the brand: FNSF, by ad agency WCIE. This advert was designed to remind people that ignoring domestic violence in our communities is perpetuating it. While these are admirable intentions, the image is disturbing and could be traumatizing to those who have experienced IPV. The main tactic is shock value in seeing the group of white people of all ages stood around in funereal dress, presumably because the woman will be killed, and the bystanders could be preventing her death. The image is victimizing and again it focuses on extreme violence with obvious evidence – in this case the woman’s death.

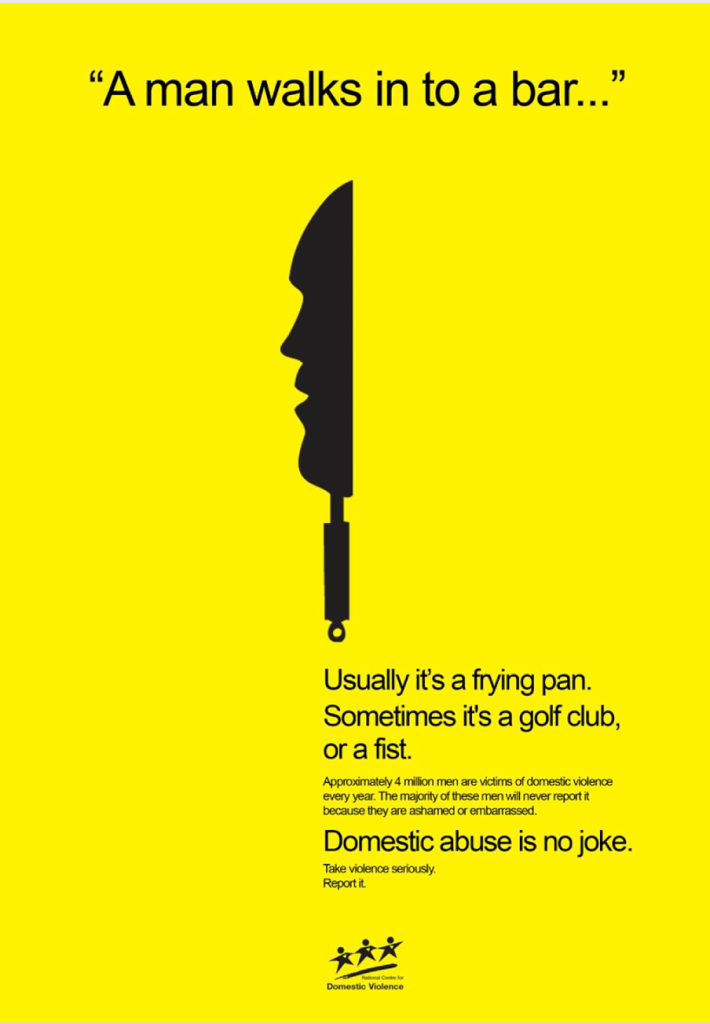

The problems of this next message regarding domestic violence against men has something is common with the “Asking for It” campaign: a lack of sensitivity. The advertisement tries to use a joke as a surprise, turning around the meaning so that the joke turns into a serious commentary on IPV. However, the comic image of a man’s face imprinted on a frying pan undercuts the message, and it is not so easy to overturn the tone once it has been set by these aspects of the design. The text asks us not to present domestic abuse as a joke, but it has already presented it as one, and the brief work it does fails to overturn the powerful assumptions in jokes made about men suffering violence.

Perhaps the problem here is that public messages about sexual or domestic violence are not the place for gimmicks or strategies typically used in the industry. It’s not just about having views or likes. There needs to be greater sensitivity and thought put into campaigns so that they do not impact viewers negatively – it’s a big responsibility! One supportive comment on the campaign noted “And as a marketeer – you have to be provocative to gain attention.” It’s true that the campaign is getting attention but it mainly seems to be from people who have experienced violence and are reeling from confronting these images. That’s not the audience that the campaign wants to reach and certainly not to harm!

You must be logged in to post a comment.